lately

strange to find oneself with words in the middle of discovery. . .

in lorca’s poetry one dances with the eternal symbols; the poet does not seek to change them or to elaborate their longstanding significances—he simply lets them do the work of enriching the verses and the lines with historical matter, with metaphorical density and abstract weights of imagination’s long compendium. evoking that sense of present and past being held in the same space of emotions and ever-unchanging questions. the moon, the night, the blood, the water—they join us through their resonance to the reality of their invented meanings.

when lorca said that “Every art and every country is capable of duende, angel and Muse,” I wonder which of these three altars I’m most drawn to. he said that the angel is light, the muse is form, and the duende is that fallen boundary between life and the darkness. to search for an ars poetica I think first of william kistler: “and still / strange, these different and strange turns / coming towards us, each alive as it / was there to uncover something hiddden, / growing, and needing to be lived to be / understood.” and then I also think of charles wright: “I write poems to untie myself / to do penance and disappear / through the upper right-hand corner of things, to say grace.” and then of wallace stevens: “the actor is / a metaphysician in the dark, twanging / an instrument, twanging a wiry string that gives / sounds passing through sudden rightnesses, wholly / containing the mind, below which it cannot descend, / beyond which it has no will to rise.” and then also of darwish: “there is enough of unconsciousness / to liberate things from their history. and there / is enough of history to liberate unconsciousness / from its inevitable ascension.” and also of rukeyser: “no more masks! no more mythologies! // for the first time, the god lifts his hand, / and the fragments join in me with their own music.” everything in there is a process—a searching that is a becoming, an all-encompassing liminality. so the poem is not something that spurs between the triangular formations of angel, muse, and duende, but something that seeks to cohere, however temporarily, all that they represent and the infinitude between them.

it reminds me of george seferis’s work: “such are the fragments of a life that was once whole, pieces that overwhelm us, that lie close to us, that, for a brief moment, belonged to us, and then became mysterious and unapproachable, like the lines of a rock sculpted by the waves or of a shell at the bottom of the sea.” writing within the land that is innately set in our minds as a theatre of the greatest western dramas, he can conjure up the mystics and the past’s grandiosity with less falsity and more automatism. they swirl beside him. they look him in the eye.

and of course seferis saw the great distance between himself and the ancients as always an illusion, as sensuality and imagination (fortified always with actual remnants and the eternal qualities of sunlight and sea-water) draws everything closer into a prolonged sentence. . . “Our pressing question is not so much to know what things have ended as to know how we, who are still alive, are to replace them, those things we believe have ended in destruction and change, as happens in every aspect of life.”

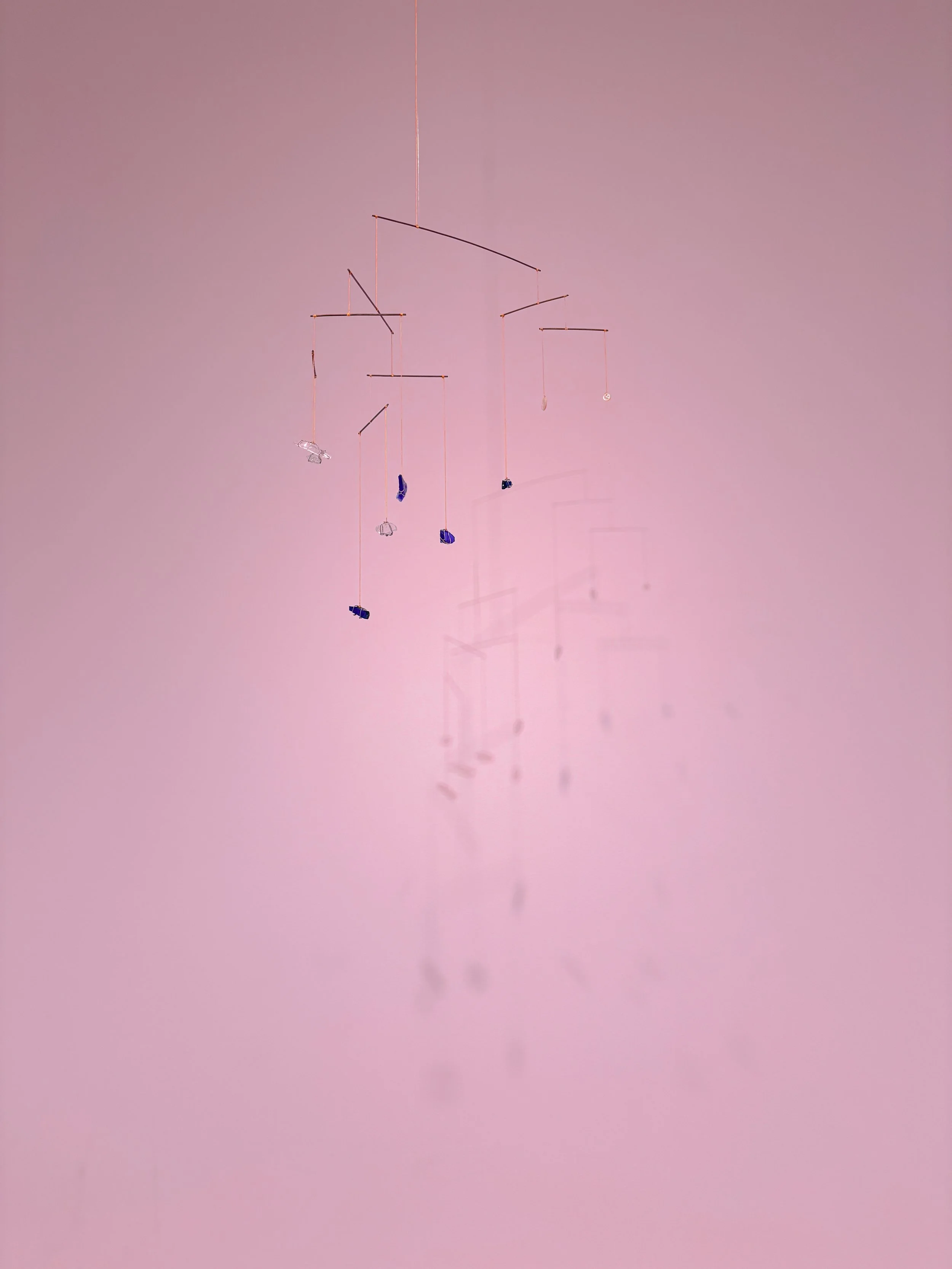

when looking at gerhard richter’s clouds one is reminded of the prolific effect that their appearance have had on our letters, our moods, our creations, and our actions. their immediate conjurings of ephmerality and texture, a phenomena depleted of their science to be transported instead as our incarnations of spirituality. to paint a cloud is to be at the mercy of a realm not of our own—a purely incidental catalyst. the cloud atlas has its own poetry, a testament to description and observation. and even the word cloud itself comes from the word for earth, an antonymic possibility that we grasp at to wrestle the untouchable back into our own plane of physical knowledge. the landscape never belongs to us, but you would never know that from the works of all humanity.m

miłosz translated by robert hass—the combinations!

How many times I have floated with you,

transfixed in the middle of the night,

hearing some voice above your horror-stricken church;

a cry of grouse, a rustle of the heath were stalking in you

and two apples shone on the table

or open scissors glittered and

we were alike:

apples, scissors, darkness, and I

under the same immobile

Assyrian, Egyptian, and Roman

moon.

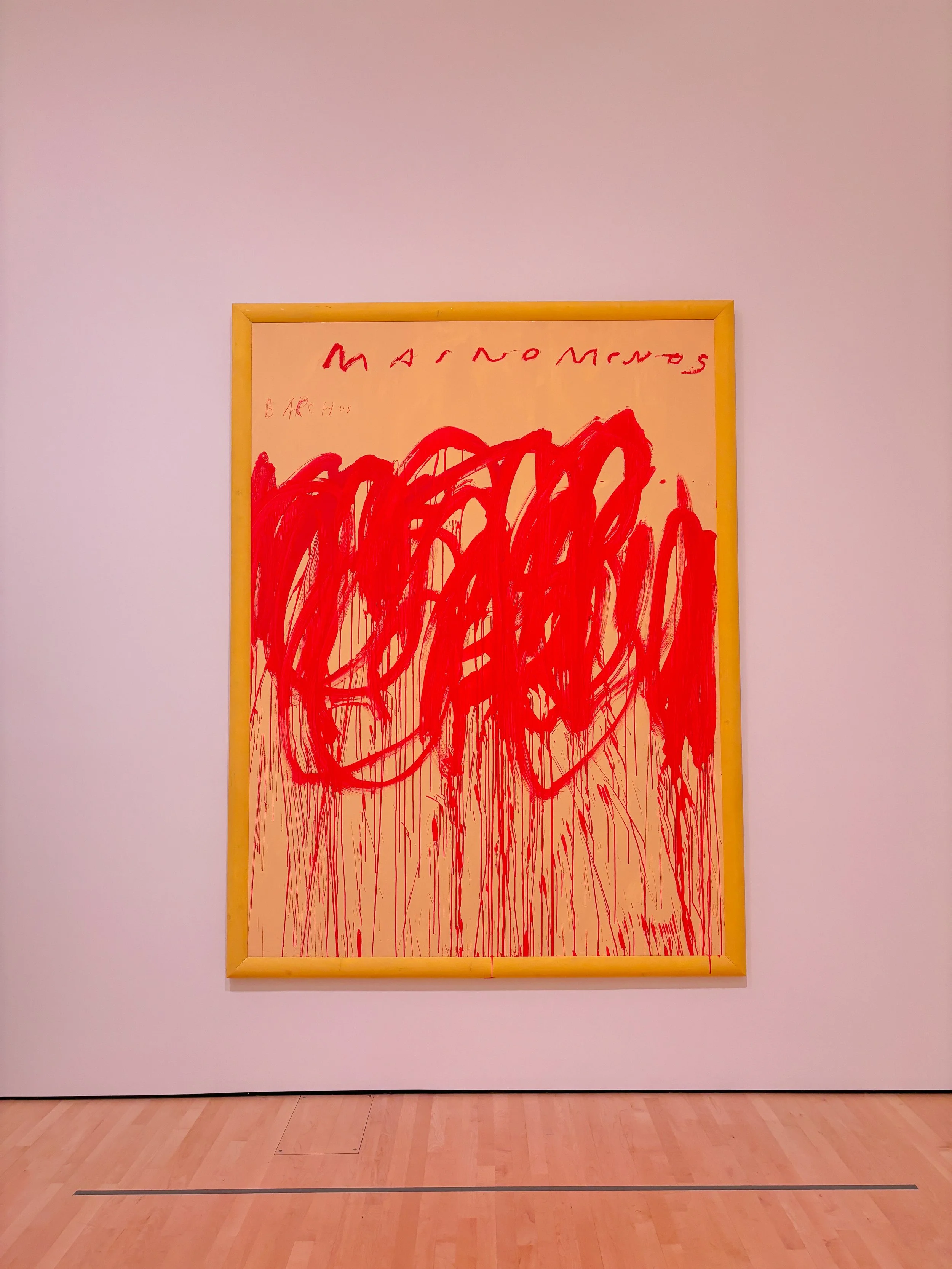

t.j. clark on poussin is one of the most elevated examples of the critic translating visual dimensions into language, which is flat but fractal on the page: “This is an artist uncannily aware of the spaces that lie between figures, stranding and silhouetting them. Time and again, in scenes that pullulate with bodies and buildings, he manages to install a governing, all-pervasive emptiness, pressing in on the human from the mineral and vegetable world. We reach out, we regularise, we raise up.” it’s astounding what he says about the painter laying our human bodies flat to the earth, to emphasise and mesmerise with that confounding boundary.